India’s currency plumbed record lows this week as investors withdrew money from emerging markets (Photo: Financial Times)

A not-so-sobering look into the immediate future of emerging market darlings who have lost their lustre as investors ponder life without US quantitative easing. Even more worrying considering the possible impact for IBSA countries.

India, 1991. Thailand and east Asia, 1997. Russia, 1998. Lehman Brothers, 2008. The eurozone from 2009. And now, perhaps, India and the emerging markets all over again.

Each financial crisis manifests itself in new places and different forms. Back in 2010, José Sócrates, who was struggling as Portugal’s prime minister to avert a humiliating international bailout, ruefully explained how he had just learned to use his mobile telephone for instant updates on European sovereign bond yields. It did him no good. Six months later he was gone and Portugal was asking for help from the International Monetary Fund.

This year it is the turn of Indian ministers and central bankers to stare glumly at the screens of their BlackBerrys and iPhones, although their preoccupation is the rate of the rupee against the dollar.

India’s currency plumbed successive record lows this week as investors decided en masse to withdraw money from emerging markets, especially those such as India with high current account deficits that are dependent on those same investors for funds. Black humour pervaded Twitter in India as the rupee passed the milestone of Rs65 to the dollar: “The rupee at 65 – time to retire”.

The trigger for market mayhem in Mumbai, Bangkok and Jakarta was the realisation that the Federal Reserve might – really, truly – soon begin to “taper” its generous, post-Lehman quantitative easing programme of bond-buying. That implies a stronger US economy, rising US interest rates and a preference among investors for US assets over high-risk emerging markets in Asia or Latin America.

The fuse igniting each financial explosion is inevitably different from the one before. Yet the underlying problems over the years are strikingly similar.

So are the three principal phases – including the hubris and the nemesis – of the economic tragedies they endure. No one who has examined the history of the nations that fell victim to previous financial crises should be shocked by the way the markets are treating India or Brazil today.

First comes complacency, usually generated by years of high economic growth and the feeling that the country’s success must be the result of the values, foresight and deft policy making of those in power and the increasing sophistication of those they govern. Sceptics who warn of impending doom are dismissed as “Cassandras” by those who forget not only their own fragilities but also the whole point about the Trojan prophetess: it was not that she was wrong about the future, it was that she was fated never to be believed.

So high was confidence only a few months ago in India – as in Thailand in the early 1990s – that economists predicted that the local currency would rise, not fall, against the dollar.

Indian gross domestic product growth had topped 10 per cent a year in 2010, and the overcrowded nation of 1.3bn was deemed to be profiting from a “demographic dividend” of tens of millions of young men and women entering the workforce. The Indian elephant was destined to overtake the Chinese dragon in terms of GDP growth as well as population size.

Deeply ingrained in the Indian system, says Pratap Bhanu Mehta, head of the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, was an “intellectual belief that there was some kind of force of nature propelling us to 9 per cent growth … almost of a sense of entitlement that led us to misread history”.

In the same way, the heady success of the southeast Asian tigers in the early 1990s had been attributed to “Asian values”, a delusional and now discredited school of thought that exempted its believers from the normal rules of economics and history because of their superior work ethic and collective spirit of endeavour.

The truth is more banal: the real cause of the expansion that precedes the typical financial crisis is usually a flood of cheap (or relatively cheap) credit, often from abroad.

Thai companies in the 1990s borrowed dollars short-term at low rates of interest and made long-term investments in property, industry and infrastructure at home, where they expected high returns in Thai baht, a currency that had long been held steady against the dollar.

The same happened in Spain and Portugal in the 2000s, although the low-interest loans that fuelled the unsustainable property boom were mostly north-to-south transfers within the eurozone and therefore in the same currency as the expected returns. Indeed, the euro was labelled “a deadly painkiller” because the use of a common currency hid the dangerous financial imbalances emerging in southern Europe and Ireland.

Phase Two of a financial crisis is the downfall itself. It is the moment when everyone realises the emperor is naked; to put it another way, the tide of easy money recedes for some reason, and suddenly the current account deficits, the poverty of investment returns and the fragility of indebted corporations and the banks that lent to them are exposed to view.

That is what has started happening over the past two weeks as investors take stock of the Fed’s likely “tapering”. And the fate of India – the rupee is one of the “Fragile Five”, according to Morgan Stanley, with the others being the currencies of Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey – is particularly instructive. (Emphasis mine).

It is not that all of India’s economic fundamentals are bad. As Palaniappan Chidambaram, finance minister, said on Thursday, the public debt burden has actually fallen in the past six years to less than 70 per cent of GDP – but then the same was true of Spain as it entered its own grave economic crisis in 2009.

Like Spain, India has tolerated slack lending practices by quasi-official banks to finance the huge property and infrastructure projects of tycoons who may struggle to repay their loans.

Ominously, bad and restructured loans have more than doubled at Indian state banks in the past four years, reaching an alarming 11.7 per cent of total assets. According to Credit Suisse, combined gross debts at 10 of India’s biggest industrial conglomerates have risen 15 per cent in the past year to reach $102bn.

For those who take the long view, a more serious failing is that India has manifestly missed the kind of economic opportunity that comes along only once in an age.

Instead of welcoming investment with open arms and replacing China as the principal source of the world’s manufactured goods, India under Sonia Gandhi and the Congress party, long suspicious of business, has opted to enlarge the world’s biggest welfare state, subsidising everything from rice, fertiliser and cooking gas to housing and rural employment.

Former fans of her prime minister, Manmohan Singh – who as finance minister liberalised the economy, ended the corrupt “licence Raj” and extracted India from a severe balance of payments crisis with the help of an IMF loan – could only shake their heads when he boasted last week that no fewer than 810m Indians would be entitled to subsidised food under a new Food Security Bill.

The bill is a transparent attempt by Congress to improve its popularity ahead of the next general election, but the government’s critics are horrified at the idea of offering Indians more handouts rather than creating the conditions that would give them jobs and allow them to buy their own. The resulting strain on the budget may also worsen the risk of “stagflation”, a toxic mixture of economic stagnation and high inflation.

India’s annual growth rate has already halved in three years to about 5 per cent and could fall further towards the 3 per cent “Hindu rate of growth” for which the country was mocked in the 1980s.

If currency declines and balance-of-payments difficulties develop into a full-blown financial crisis in the coming months, India will be propelled unwillingly into the third and final phase of the trauma.

Phase Three is when ministers and central bank governors survey the wreckage of a once-vibrant economy and try to work out how to rebuild it.

It is traditional for those governments that survive, and for the ones replacing those that do not, to announce several false dawns and to see “green shoots” that turn out to be illusory.

It is hard when times are bad to impose financial discipline that would have been easier to apply before. Indian policy makers are already torn between the need to lower interest rates to boost growth and the necessity of raising them to protect the rupee and tackle inflation – the same kind of tension between austerity and easy money that has afflicted developed economies since 2008.

India’s underlying economy is nevertheless sound and its banks are safe, say Mr Chidambaram and other senior officials. There is therefore no need to contemplate asking for help from the IMF or anyone else.

Mr Sócrates said much the same in Lisbon three years ago. “Portugal doesn’t need any help,” he said, almost leaping from his chair. “We only need the understanding of the markets.” The markets did not understand, and Portugal did need the help.

Source – Victor Mallet of the Financial Times August 23, 2013

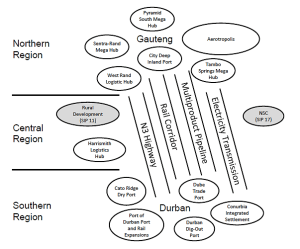

According to the recently released HSBC Trade Forecast Report, by 2020 India is expected to surge past the United States as the world’s biggest importer of infrastructure goods – a position it is expected to hold until at least 2030. This is a result of the country’s increased demand for materials for infrastructure projects (i.e., metals, minerals, buildings and transport equipment) as it invests more in the building of its civil infrastructure.

According to the recently released HSBC Trade Forecast Report, by 2020 India is expected to surge past the United States as the world’s biggest importer of infrastructure goods – a position it is expected to hold until at least 2030. This is a result of the country’s increased demand for materials for infrastructure projects (i.e., metals, minerals, buildings and transport equipment) as it invests more in the building of its civil infrastructure.

You must be logged in to post a comment.