Ever since the inception of automation in Customs (circa 1981) it has offered time-saving benefits and obviated several mundane tasks. Like all things new, improvements are lauded and soon forgotten as quickly as the novelty wears off. With each improvement more ‘operational knowledge’ is translated into software code, aiding the user, but unwittingly depriving future users of fully understanding the logic behind it all.

Let me provide an analogy –

20 years ago most broker’s classified supplier’s invoices for appropriate tariff, computed currency conversion, value for duty purposes and duty calculation all manually. Similarly, Customs officers verified each declaration according to the supporting documents presented. True this was resource intensive and time-consuming, and hopelessly inefficient by today’s standards and expectations. On the plus side, the brokers and customs officials had a greater appreciation for the detail and technicalities involved in clearance processing. Another benefit of the past was the accessibility of the customs officer.

After 2 decades of computerised enhancements the technicalities around customs clearance have been made easier through significant automation of workflows and communication. Most brokers nowadays offer transport and logistics services and have clearly evolved into international freight forwarders. The introduction of the Customs duty deferment scheme has also long been recognised by most brokers and forwarders as a critical component of the financial viability of their business.

In fact, the nature and focus of the trade and customs business have themselves shifted drastically in the last 10 years. Company boardrooms are more about strategy and tactics, and the IT division plays more and more an operational role rather than purely a support function. This is often the bain for the operations division which fails to realise that ICT is an ally not and enemy. This short-sightedness is also the cause by which the system is often blamed for operational shortcomings.

It is therefore clear that procedural enhancements, revised business practices along with computerisation have all lead to a conglomeration of miscellaneous ‘detail’ which seemingly daunts the user. The computer is able to process millions of lines of code and perform instructions across the physical boundaries which make up the different organisational divisions and data stores. In the past human intervention gave effect to physical processes through manual activities with hand-offs from one division to another; today, thousand’s of instructions are triggered by a few swift keystrokes by an operator, where sophisticated algorithms filter and distribute data, perform calculations, risk assessment and account management. Computerisation also enables activities to occur in parallel, whereas a manual process normally follows sequentially. Because the eye does not see these things the user/operator is unaware of the sequence or complexity of the processes being accomplished. Because there is perhaps more idle time today, the expectation is that things need to happen in seconds, not hours or days. And so, service levels are defined with these expectations in mind with onerous penalties for non-delivery. (Okay, Customs is indemnified against the latter!)

In the light of the above and a review of the recent weeks of activities leading up to the implementation of the first phase of the Customs Modernisation Programme, it is abundantly apparent that the state of preparedness needs to look at a variety of areas, not just those which affect the computer operator (customs officer or trader).

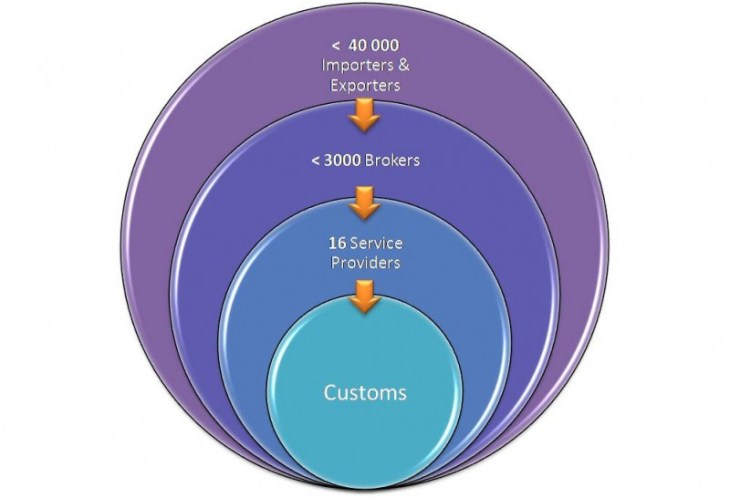

The diagram is intended to illustrate the effect of Customs Modernisation on the local trade community. In terms of technical ICT developments, Customs need only interact with the 16 service providers. These in turn have the responsibility to provide systems and systems support for their 3000 or so brokers and freight forwarders. However this obligation can only impart systems knowledge. The brokers/freight forwarders must, over and above the systems enhancements, be able to articulate and understand these changes in a tangible manner. Why, because these affect not only their legal obligations under the law but their service offerings to their clients – the importers and exporters. This is where I perceive there is some gap or lack of capacity rather. There are indeed excellent thinkers in this industry, but alas too few, and these few have fulltime day jobs as well. A change of the current magnitude requires a dedicated team of knowledgeable practitioners who (on a fulltime basis) should not only challenge the law makers but make constructive alternatives. It is difficult to maintain focus on this if the participants are all volunteers.

Lastly, those thousands of importers and exporters are soon to realise that the impending new Customs Act has a whole bag of goodies for them too! While the umbrella organisations have always had the intent to provide training, this requires capacity as well. The recent joint training initiative between SARS and Stakeholders was undoubtedly a first, but must not be the last. Moving forward it is imperative that similar joint ventures occur, with increasing frequency and more detailed training content and materials. There is more than enough room for all of us (SARS and Trade) to make an impact. This is the bigger picture!

You must be logged in to post a comment.